Philanthropy in Action:

Peter Sim, MD

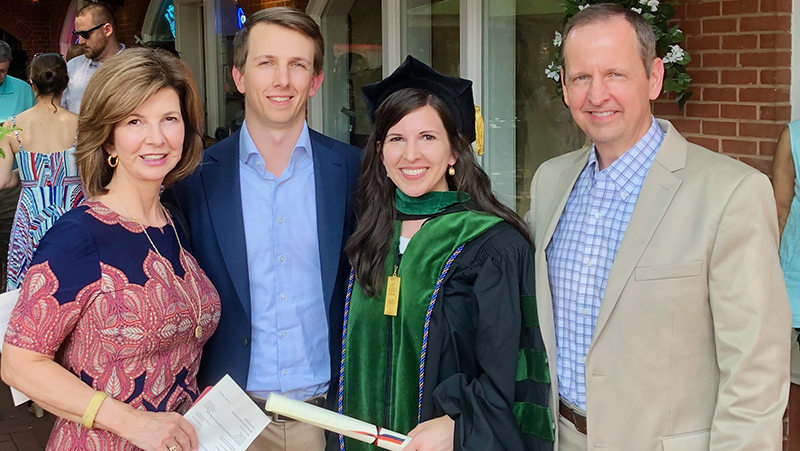

A gift to his father inspired Peter Sim, MD '73, and his wife, Anna, to support a scholarship and invest in future medical students

During the depths of the Depression, Alan Sim was pursuing a college degree in mechanical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology when his money ran out.

Alan was already helping to pay the tuition for his brother, a medical student, and had to quit his night-shift job on an assembly line because of college regulations. To complete his degree, he asked for and received a $50 loan from the archbishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, where Sim had served as an acolyte. When he tried to pay it back a year later, the bishop declined. Instead, he said, “Please remember what was done for you, and do the same for someone else.”

Peter Sim, MD ’73, and his wife, Anna, took the words from his father’s story to heart when they considered their philanthropic priorities. The story spans a period before Peter and Anna were even born, and now it has come full circle.

Runs in the Family

Growing up, Peter Sim wanted to be an engineer like his dad, but the summer after his freshman year at Carleton College, he worked as an orderly in a hospital emergency department. He had one year of college and no medical training, but because the ED was so small (“10-foot square with three cots separated by curtains”) and Peter was the first person every patient saw, he got an on-the-job education.

After he graduated, his older sister, Martha Ann Sim (Nurs ’68), then a nurse at the University of Virginia, recommended he consider UVA for medical school. As a runner, the first things he noticed were the spectacular trails and temperate climate of Charlottesville. He had interviewed at large city medical schools (and one where his annual in-state tuition would be $350), but after visiting, UVA shot to the top of his list. Reflecting on his medical school experience today, what resonates most are the experiences he had with extraordinary faculty like the late Professor of Pediatrics Elsa Paulsen, MD.

“She once took a number of us on a field trip in rural Greene County,” he recalls. “She said, ‘I think you need to know where some of our patients live,’ so we went out on a secondary road and turned off onto a dirt road. We were in a van, and I didn’t think we’d make it up the hill. We went down into a valley, and you saw smoke coming up from the chimneys, people pulling the curtain to see who’s driving by. She said, ‘These are our patients, OK? You need to know what their home environment is like.’ That had an impact on me.”

A few years later, Peter was doing a three-year residency at a hospital where a young woman named Anna Cain had received a two-year scholarship for a lab tech program. She injured her head on a machine and was sent to the ED, where Peter treated her. “It was not love at first sight,” she quips. Yet a mutual friend who was also a resident later told Peter, “I think you might really like her.” Both were avid athletes (he a marathon runner, she a triathlete) with a penchant for travel and, as they would discover, an underlying interest in sharing their good fortune with others.

Anna received a Master’s in Museum Studies and Art History and became an appraiser. Peter made a transition from primary care to emergency medicine. “I saw a lot of people who had health problems they had neglected for a long time because they didn’t have the resources,” he says. “One of the things I really love about emergency medicine is ‘We’ll see you no matter what.’”

It’s that empathetic ethos that led him to volunteer at Victory Junction in North Carolina, one of the original Hole in the Wall Gang (now SeriousFun) camps for children with critical illnesses founded by Paul Newman. In 2005, he became its first medical director from outside of the pediatric hematology/oncology field. Given the range of campers’ medical conditions, Peter’s background in emergency medicine turned out to be the ideal fit.

“We had kids on their second heart transplant, kids on ventilators—and it’s all free,” Peter recalls. He served there for five years and describes it as “an absolutely phenomenal experience.”

On the Same Page

Whether he is working with physically challenged children or economically disadvantaged adults, there is a clear through-line in Peter Sim’s perspective. “I’ve always had a soft spot for those who are less advantaged. That would transfer over laterally to students who are interested in medicine,” he explains. “I feel blessed that I didn’t graduate with tens of thousands of dollars or more in debt, and I’m eternally grateful to my parents.” His mother was a secondary school teacher, and his father prioritized education.

After 49 years of marriage, Peter and Anna tend to finish one another’s sentences, and when it comes to philanthropic priorities, they are clearly on the same page.

In considering different causes, investing in future medical students “seemed the best fit overall,” says Anna. “We wanted to give this opportunity to as many people as possible in perpetuity.”

The Sims’ motivation is driven by a sense of responsibility: “For those of us who are privileged enough to make a decent amount of income during our professional lives, I just think it’s an obligation to do the same for others who are coming behind us,” Peter says. “You’re not only helping that individual who is getting that scholarship but funding the thousands they will care for in their professional career.”

The Sims have made a seven-figure provision from a portion of their estate to establish a merit scholarship. Open to all, the Peter Alan Sim, MD and Anna Cain Sim Scholarship will annually support a minimum of two medical students. Every recipient will be given the story of the individual who inspired the award.

“My dad was always a champion of education, and he died in 1987,” Peter says. “What better way to memorialize him than to create a scholarship in his honor?”